14.5, 18 or 51 percent - can livestock be blamed for climate change?

- Venni Arra

- Nov 18, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 5, 2019

Friday evening I attended the Sustainability Symposium organized by the UCL Climate Action Society. Eight expert panelist speakers from different disciplines delivered short, powerful talks on various aspects related to climate change and sustainability. After this event I felt inspired by the “Rebellion Day” the following day, organised by the non-violent direct-action movement: Extinction Rebellion.

Together with some of my course mates, we made our way to Waterloo Bridge in central London to join other protestors in demanding urgent action on climate change. Amongst most banners reading rebel for life, fossil fuel era over I did catch a few banners reading vegan for the planet.

The increased build-up of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere has led to significant impacts on the global climate system, and agriculture plays a key role alongside industry, transportation, buildings and heat/electricity production in contributing to this increase. In different parts of the supply chain, the livestock industry emits greenhouse gases such as methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide with varying impacts on the environment and the climate system (Figure 1).

Methane (CH4) accounts for the largest part (44%) of the livestock industry’s emissions and is produced as part of the digestive process of ruminant animals called enteric fermentation as well as through manure management. It is around 30 times more potent compared to carbon dioxide but a short-lived greenhouse gas, which means that it dissipates from the atmosphere within 10 years. Consequently, the presence of methane warms the planet up quickly but for a relatively short period of time.

Nitrous Oxide (N2O), on the other hand, is a long-lived greenhouse gas mainly produced during the storage and processing of manure as well as in the production and usage of both organic and synthetic fertilisers for producing feed. It accounts for 29% of the livestock industry’s emissions and is the most potent greenhouse gas out of the three, being 300 times more potent than CO2.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is also a long-lived greenhouse gas and accounts for 27% of the livestock industry’s emissions. It originates from the expansion of agricultural land, leading to deforestation and changes in land use, as well as from the production, processing and transportation of animal products.

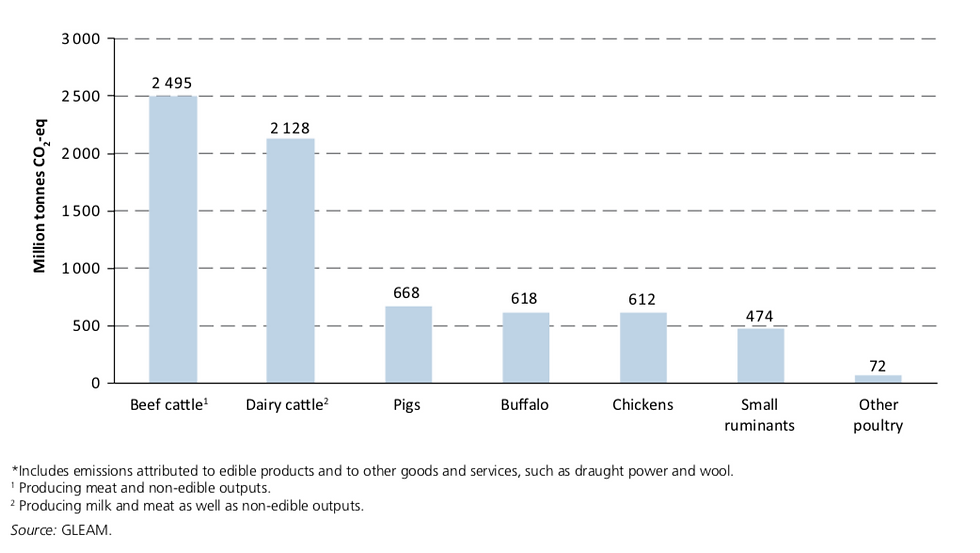

Out of all farmed animals, beef and dairy cattle are the largest emitters because of their high overall number, big size and the digestion process producing methane (Figure 2). As a result, different dietary shifts have been recommended, such as the Mediterranean diet in which high-impact beef is replaced with fish and poultry. These diets lower one’s environmental footprint and can be regarded an “easier” shift compared to a strictly plant-based diet, considering the cultural, personal and social connection to the average western meat-heavy diet. However, since even the lowest-impact animal-based products typically exceed the environmental impact of the highest-impact vegetable substitutes, the positive impact of fully plant-based diets should not be overlooked.

But by how much does animal agriculture really contribute to the global greenhouse gas emissions?

The currently widely used estimate of 14.5% refers to the FAO report Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock published in 2013. Seven years earlier in 2006, however, the FAO claimed that the livestock industry was responsible for 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions in their influential study Livestock’s Long Shadow. This report was criticised by academics from the Department of Animal Science at the University of California, claiming that a full lifecycle assessment was only used for the livestock sector and, therefore, wrongly compared to the transportation sector. This led to a reinvestigation, and the FAO updated the data as well as revised the framework correcting 18% to 14.5%.

A year before the second FAO report was published, a partnership between the FAO and the meat and dairy industry was announced in order to “improve how environmental impacts of the livestock industry are measured and assessed”. The report criticising the initial FAO report was also funded by the Beef Checkoff Program and was a collaboration between agricultural organisations and the authors from the University of California. Critics of the FAO report point out the problem in having a report authored by livestock specialists instead of environmental assessment specialists.

Conversely, an assessment published by the Worldwatch Institute in 2009, led by environmental experts from the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, claims that the livestock industry is responsible for a staggering 51% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This figure was also used in the documentary Cowspiracy. By using a full lifecycle assessment, including direct and indirect emissions, they claim that sources such as land use, methane and respiration of tens of billions of livestock animals were vastly underestimated and even overlooked in the FAO report from 2006. Critics have pointed to the controversy in adding animal respiration in the calculations as well as in dismissing the carbon sequestration potential of agricultural lands.

The debate around the contribution of animal agriculture to global greenhouse gas emissions is ongoing, and the real number is probably somewhere in between 14.5 and 51%. The discrepancies can partly be attributed to differences in methodologies and disagreements in the use of sources for greenhouse gas emissions. It is not easy to estimate the total emissions from the livestock sector because of the variety of production systems resulting in different emission concentrations for the same product.

Whether the actual number is 14.5, 18 or 51%, the livestock sector is a significant contributor to the global greenhouse gas emissions and should be tackled as such. Some recent studies have suggested an introduction of environmental labels and the taxation of meat and dairy products to reduce the environmental impact of the livestock sector. Could this potentially curb the rising demand for meat and dairy consumption?

Hey! Thank you for the comment.

Great to hear that you have cut down on meat, and especially cattle products since they are very detrimental for the environment. This will definitely lower you environmental footprint! If you haven't found a favourite plant-based milk yet from the regular soy, almond, coconut and oat milks, I would suggest you give rice, hemp, cashew, hazelnut, walnut or macadamia milk a try. Maybe you'll find a new favourite amongst these - my personal favourites are soy, rice and hemp :)

You are absolutely right, the livestock industry is important for economies around the world, and is one of the fastest growing sectors in the agricultural economy according to FAO. A transition away from an…

Great read Venni!

I myself do try and keep away from cattle products; I find it relatively easy as I do not particularly like steak anyway! I also try to have a few vegan/vegetarian days a week. At the moment I am trying to find an alternative to cows milk which is proving tougher as I do like it on my cereal in the morning!

Obviously the cattle industry is huge and a large amount of people rely on it; I read that over $6 billion worth of beef is exported from the U.S. annually. This made me wonder how such a large transition that is needed away from this industry would impact the global economy and what could replac…